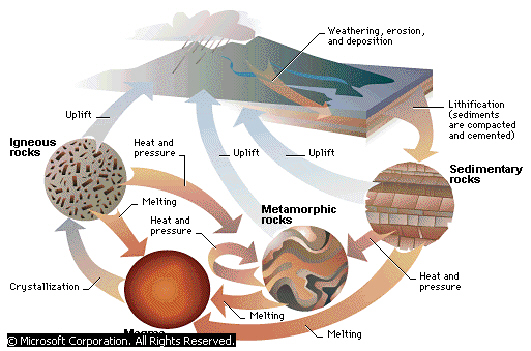

Animal and plant life on Earth slowly evolved in response to changing conditions on our planet. There is also an even slower evolution of rock material under the changing physical conditions at or beneath the earth's surface. This is called the Rock Cycle. In the rock cycle, each of the three principal types of rock, sedimentary, metamorphic, or igneous, can evolve into either of the two other types of rock or even into other rocks of its own type. For example, a rock may change into a sedimentary rock by eroding, and then accumulating as sediment in a new place, and then cementing into rock. Metamorphic rocks form when rock is heated or subjected to high pressures, or both, without melting, and igneous rocks form when rock melts and then cools again.

The

rock cycle shows how each of the three principal types of rocks

(sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous) can evolve into either of the

two other types of rock, or even into other rocks of its own type.

Sediments that are compacted and cemented form sedimentary rocks,

rocks that are subjected to heat and pressure form metamorphic rocks,

and rocks that are melted and then cool form igneous rocks.

The

rock cycle shows how each of the three principal types of rocks

(sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous) can evolve into either of the

two other types of rock, or even into other rocks of its own type.

Sediments that are compacted and cemented form sedimentary rocks,

rocks that are subjected to heat and pressure form metamorphic rocks,

and rocks that are melted and then cool form igneous rocks.The rock cycle transforms rocks from one type to another, or to a new rock of the same type, depending on the temperature and pressure where these transformations occur. These conditions, in turn, depend on the depth at which the transformations occur. Weathering and erosion, which break down rocks and create sediments, occur at or near the earth's surface. Compacting and cementing of sediments to form sedimentary rocks usually starts at depths from about 0.6 to 2 miles. Most metamorphism, the process of forming metamorphic rocks, occurs at depths of between about 6 to 18 miles. Magma, or molten rock, often forms at depths below 18 miles, but magma may then rise before it solidifies. Igneous rocks can form at any depth, even at the earth's surface. Igneous rocks that form at the earth's surface are termed volcanic.

Any rock transforming into a sedimentary rock would begin its

transformation by cropping out on the earth's surface, where it would

weather and erode into sediment. Gravity, water, glacial ice, or wind

would eventually remove the sediment from the outcrop and deposit it

somewhere else. The sediment would likely be eroded and deposited

again and again until it ended up in an environment that was

accumulating sediment instead of eroding. There, the sedimentary

particles would be buried by subsequent accumulations of sediment.

When the sediment becomes buried under about 0.6 to 2 miles of

overlying sediment, the  pressure

of the overlying sediment compacts the sediment and causes minerals

to precipitate, which cements the sediment into sedimentary rock. In

this way, any of the three types of rock could evolve into a

sedimentary rock.

pressure

of the overlying sediment compacts the sediment and causes minerals

to precipitate, which cements the sediment into sedimentary rock. In

this way, any of the three types of rock could evolve into a

sedimentary rock.

If enough sediments accumulate on top of a rock, it takes a different path through the rock cycle and becomes a metamorphic rock. This metamorphic rock forms as the original rock is pushed deeper into the earth's crust and becomes hotter. The sedimentary rock shale, for example, consists primarily of clay particles. During metamorphism, these clay particles recrystallize into microscopic-sized crystals of mica, a plate-shaped mineral. If metamorphism stops at this point, the resulting rock is a slate. With increasing temperature, however, mica crystals increase in size to form the metamorphic rocks phyllite and schist. Additional heat can cause other minerals to form and segregate into different colored bands, resulting in the metamorphic rock gneiss.

A rock undergoing metamorphism may experience even higher temperatures and begin to melt. If the resulting magma makes its way to the earth's surface in a volcanic eruption, it will form an extrusive igneous rock that will be susceptible to weathering and erosion. Alternatively, the magma might cool and crystallize beneath the surface as an intrusive igneous rock. This igneous rock, in turn, could follow one of three paths in the rock cycle: It could experience another increase in temperature and pressure conditions and form a new metamorphic rock; it could remelt, and on cooling, form a new igneous rock; or it could be brought to the surface and exposed to erosion, leading to the formation of a new sedimentary rock.

Contributed By:

Martin Gregg Miller

Article from Microsoft © Encarta Encyclopedia 99